A project at Providence Health Care aims to take the hospital food tray and turn it into a platform for culturally appropriate care for Indigenous patients.

The objective of the project, called Exploring Indigenous Foodways at PHC, is to better understand the food experience of Indigenous patients and learn how to improve it. The eventual goal is to modify the menu at St. Paul’s Hospital – and then at facilities throughout Providence – to provide traditional foods to improve the outcomes and experiences of Indigenous patients.

Food as a vital part of the human experience

“Food is a significant part of our mental, emotional, and spiritual experience as human beings and that doesn’t change when we’re hospitalized. If anything, it becomes even more significant,” says Victoria Janzen, Clinical Dietitian at St. Paul’s Hospital, operated by Providence.

Providing culturally appropriate food (something Providence Health has offered Asian patients for more than 25 years) is considered so important that the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada stated that “to deny one’s food is to deny them of their culture.”

The healing power of food

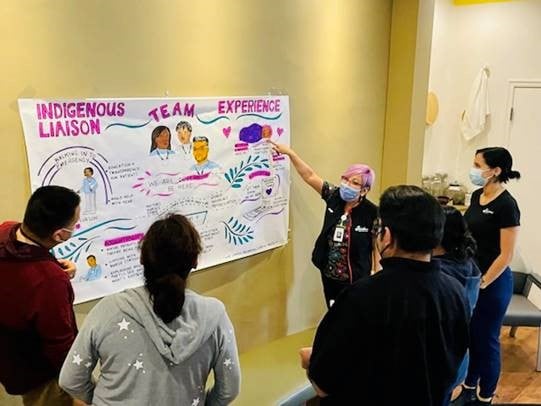

“Food is integral to healing and patient wellbeing,” says Sheri Hundseth, Director of Indigenous Reconciliation and Community Engagement at Providence. Hundseth’s team is tracking the experiences of Indigenous patients in a project called Patient Journey Mapping.

“In this work, the importance of having traditional Indigenous foods has come up repeatedly,” she says. “Patients have suggested a number of traditional foods including Pacific salmon, venison, Indigenous herbs, teas, bannock, fresh fruit, and berries – amongst others.”

Food as a matter of cultural safety

Traditional food means not only offering Indigenous patients a familiar form of nourishment or even traditional medicine. It can also be a matter of cultural safety. Just coming into a hospital can be a difficult experience for Indigenous peoples who have direct or inter-generational trauma from experiences with residential schools or former Indian hospitals.

Traumatic memories can be triggered by such things as odours, bright lights – and even food.

“We want to offer Indigenous patients meals that help them feel safe and respected – to help them feel that their culture is acknowledged and celebrated here,” says Janzen.

The project is following the framework developed by Nourish Leadership, a national organization based on the belief that food is fundamental to patient, community and planetary health and well-being. Integrating Indigenous food into health care institutions is a key element of Nourish’s work.

“It’s time to un-learn old ways of thinking, confront biases in our institutions, and recognize the power of Indigenous foodways to transform heath care,” says Mair Greenfield, who is the Indigenous Program Manager for Nourish.

“Foodways” is a term that often refers to the intersection of food in culture, traditions, and history. Nourish’s work has demonstrated that the key to offering culturally safe and appropriate Indigenous foods in hospitals is to build relationships and engage with stakeholders. That’s why the four-member project team is approaching its work “slowly and deliberately and – hopefully – with humility,” as Janzen describes it.

The work of Hundseth’s team with Indigenous patients is providing valuable information. Surveys are also being used. Together, these methods are helping the project team learn more about topics such as identifying traditional foods and how they are perceived as important to healing; how these foods are prepared; and views on blessing food.

There are also logistics such as sourcing food, adhering to food regulations, training staff members, and acknowledging that Providence care sites serve many distinct Indigenous peoples (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) so traditional food for one group will not necessarily be the same as for another.

St. Paul’s cafeteria could also provide Indigenous foods

The team expects to have a report that addresses these factors completed in a year, along with an action plan that will be implemented in the following years. Meanwhile, they hope the St. Paul’s Hospital cafeteria – which operates with fewer restrictions than the patient meal-tray service – will offer traditional foods to Indigenous patients and families, especially on June 21 each year (National Indigenous People’s Day).

It’s a project that needs to be carefully and comprehensively developed and yet it can’t evolve soon enough as far as team members such as Janzen are concerned.

“When we’re sick and when we’re scared – what more important time to feel that we are being taken care of and that we are somewhere we belong? Food can be a part of that.”

Learn more:

Why Hospital Food Matters for Reconciliation – video from Nourish Leadership

Truth and Reconciliation at Providence Health Care – web page

Indigenous Wellness and Reconciliation Action Plan at Providence – PDF