In honour of Social Work Week in BC and Kidney Health Month, learn more about a social worker-led patient group that helped people in need of a kidney donor get more comfortable reaching out.

It’s one thing to ask a friend for a ride to the airport or help on moving day; it’s quite another to ask them for a kidney.

And yet, for those in need of a kidney transplant, often the best and fastest way to find a donor is to have interested family members and friends tested for compatibility. But for many people, broaching the subject can feel daunting.

That was the impetus behind the Live Donation Patient and Family Group, a group for patients in need of a kidney transplant to discuss donor outreach strategies and receive education and support.

Hosted by the Providence Health Care Renal Program, the group met virtually from November 2020 to June 2022. While no longer running, it is currently the subject of a Providence Health Care Research Challenge project to evaluate its effectiveness.

Don’t ask, share

A kidney transplant is the preferred treatment option for most people with end-stage kidney disease because it offers potential benefits such as greater freedom and a longer, healthier life compared to dialysis. There are several advantages to a living donor transplant over a deceased donor transplant including better success rates and shorter waiting times.

The Renal Program at Providence supports individuals at every stage of kidney disease and St. Paul’s Hospital is one of two adult kidney transplant centres in BC.

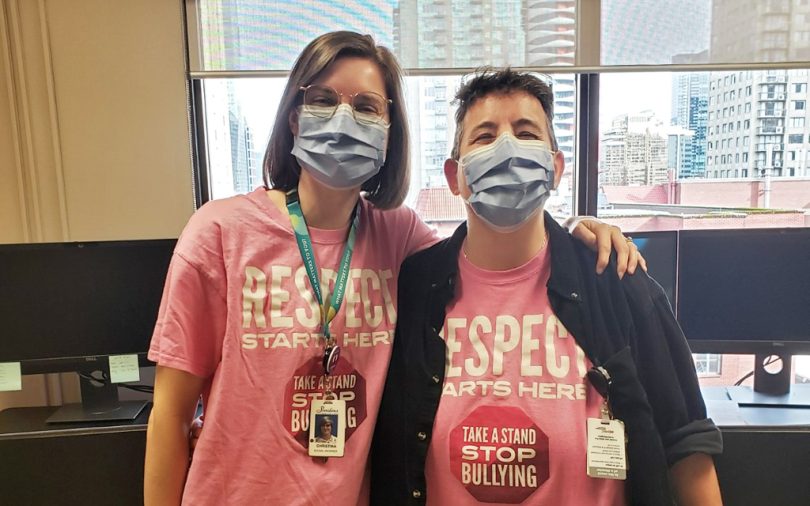

Renal Program social workers Christina Schellenberg and Jody Max initiated and led the Live Donation Patient and Family Group.

“We know that it’s really difficult for people to find a live door. It’s difficult for people to get comfortable getting the word out. We started this group in an effort to try to help people become more comfortable with that,” Schellenberg explains.

One often-discussed strategy: don’t ask for a kidney; instead, share your story. Participants were encouraged to be open and honest about their health situation and need for a donor in their daily conversations. Switching one’s mindset from “I have to ask for a kidney” to “I have the opportunity to tell my story” puts less pressure on both the individual with kidney disease and the person they’re talking to.

Find a donor champion

Another popular strategy: identify a “donor champion” – someone who can advocate on your behalf.

“It doesn’t have to be the patient who’s having these conversations, because that’s the hardest way to do it,” says Max. “It’s much easier to find somebody among your family or friends who’s willing to do that for you.”

Participants came up with plenty of other ways to reach out without being coercive: share your story in your annual Christmas letter; leverage the power of social media; and network beyond your immediate social circle.

In addition to discussing outreach, education was also a big focus of the group. Guest speakers, including nephrologists, kidney donors and transplant recipients, often joined.

“A lot of people are really afraid for the safety of the donor and a lot of people have misconceptions about donation,” Schellenberg says.

Identifying barriers to outreach and educating participants about the safety of living kidney donation went a long way toward building their comfort and confidence.

Mutual support

Support was another important element of the sessions. Each meeting started with a roundtable where participants were invited to share where they were at in their respective kidney journeys.

“It can be difficult for people waiting for a kidney to come available, or waiting for a person to come forward to donate,” says Schellenberg.

The group format allowed participants to sympathize with each other’s difficulties and celebrate each other’s positive news.

“There was really lovely mutual support that the participants would give each other,” Max recalls.

While Schellenberg and Max aren’t quite ready to share their research, early findings based on survey results have been positive.

“People expressed that, after coming to the group, they were more confident and comfortable doing donor outreach and getting the word out,” Schellenberg says. “We hope that helps with the overall goal of helping people find a live donor.”

Once the final research is complete, Schellenberg and Max hope to consider ways to revive the donor outreach group.

Related stories:

- Taking ACTION on cultural barriers to living donor kidney transplant

- One family’s story of organ donation and transplant