Melissa Faulkner

When Providence Health Care’s mental health program approached art therapist Jillian Bagan (they/she) with a pitch for a patient art show, they knew they had to do it when they heard the theme: Unmasking Mental Health.

“Masks are such a huge symbol in art therapy,” Jillian said. “They help people explore their external and internal world… what you want people to see of you and how you want people to perceive you, versus how you perceive yourself and what’s going on for you on the inside.”

Over the course of three weeks, Jillian facilitated 33 participants in creating 34 artworks that would for one week line the fourth-floor hallway of St. Paul’s Hospital (SPH). Art therapy is offered in a variety of clinical environments throughout PHC, and participants’ units spanned from the SPH eating disorder clinic, to the Parkview dementia tertiary care unit, to youth at Foundry Vancouver-Granville, amongst others. Acrylic paint and markers were the most commonly used materials, though material availability varied by unit.

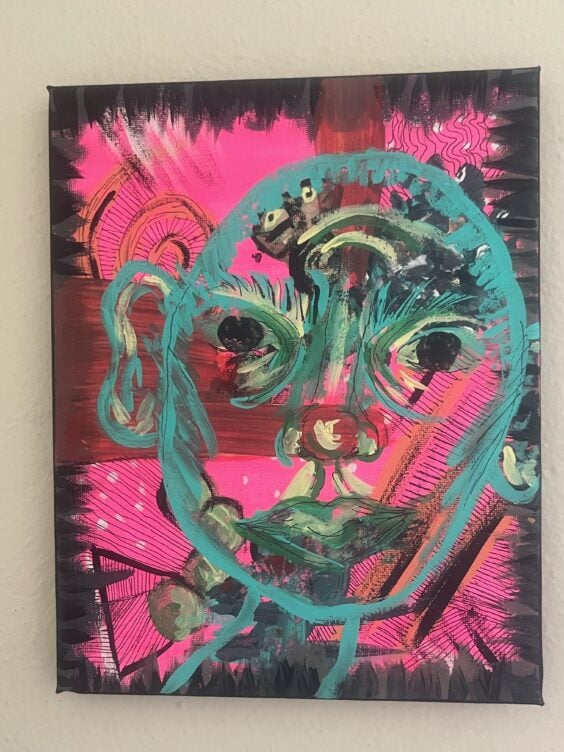

And the theme within the theme? Jillian immediately noticed a sense of duality. Masks being split into two, a hardness and a vulnerability. A few masks especially stood out to them. The first was a black and orange piece with glitter—speaking to trendiness of mental health maintenance, versus the stark reality.

“For me, mental health has become such a hot topic that sometimes there really is a glitz and glam about it, and we tend to forget the reality that people are actually really struggling.”

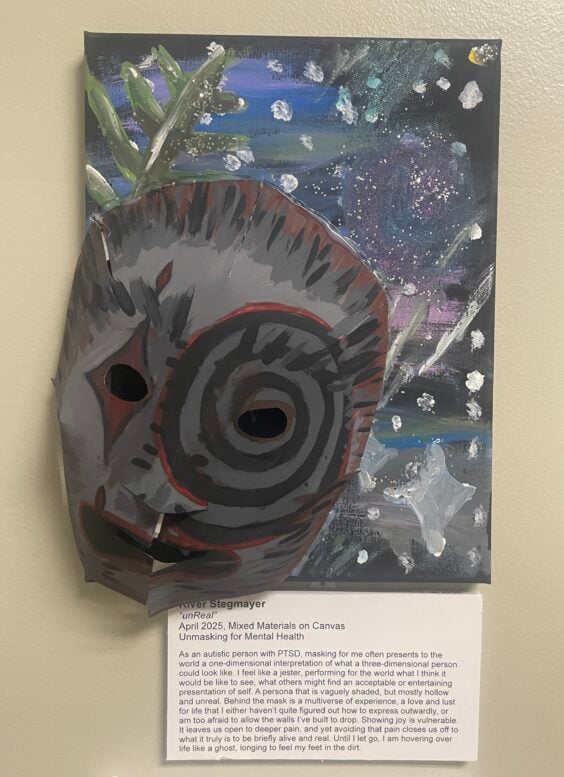

Another mask—a thoughtful paint mix of black, white, gray, red, and glitter with attached canvas—that struck them was made by River Stegmayer (they/them) during an art group session at Foundry Vancouver-Granville, which offers young people access to mental health and substance use support, primary care, peer support and social services. River’s work explored the dysfunction of overdone coping mechanisms, in this case, feeling stuck behind a protective mask that prevents you from communicating your inner world and being vulnerable.

“Even in the way that I dress is a little more hard, a little bit more dark,” River said. “Who I actually am is somebody who feels very deeply and has a very deep love for life and joy and that feels way more vulnerable. I want to keep those things sacred to me and not put them out into the open and allow me to get hurt in a deeper way.”

“For awhile when I was younger that was a really good protective mechanism. But as an adult, it makes it harder for me to have authentic connections and for me to feel comfortable or for me to experience things in the moment because I’m too busy in my head trying to control for everything.”

River moved to Vancouver from Ontario in 2022, getting in touch with Foundry Vancouver-Granville upon the recommendation from a friend after challenges with finding a doctor. A year later, River was experiencing homelessness, relying on Covenant House and Foundry Vancouver-Granville to get back on their feet. And when they did, they started attending different groups like art group and knitting group at Foundry to help them not only to set goals and build routine, but also to make friends and connections.

But eventually coming to Foundry also became about finding self-expression through art. River had always been interested in drawing and painting, even considering enrolling in art school for post-secondary. But they became so focused on the technical while experimenting with realism that they became frustrated and stopped making art entirely. For years. That is, until art therapy.

“Right around time I started going into art group, I got back into an expressive way of doing art instead and more of an abstract way,” they said. “I think it changed my relationship to art.”

And through the more expressive nature of art therapy, they found that they could explore their feelings and learn more about themselves in a healthy, effective way. Based on their experience, they especially recommend it as an option for anyone who has experienced PTSD or any kind of trauma that may be too difficult to talk about but still needs to be worked through.

And there’s a reason for that. According to show facilitator and art therapist Jillian Bagan, art therapy can make space for patients to lower their defense systems so bigger issues and feelings can come to the surface and be processed in a new way. “Sometimes we get a little stuck and it feels safe to not make any changes,” Jillian said. “But if we can make art about the change, it feels less scary and less of a risk—allowing new pathways in our brains to form. Sometimes just thinking about the change can allow us to open up to changes.”

While the neurological benefits of art therapy are well-documented, River emphasizes its emotional and societal relevance in today’s complex world.

“I think the reality of the situation that my generation, younger generations, and—honestly—all of us, is very difficult: politically, economically, ecologically,” they said. “It’s kind of a difficult and scary time to exist and there’s a lot of things to be wrapped up in and afraid of and angry about, and it’s all very real.”

“But we have to find—as a collective—a way to survive it, go through it, and still enjoy being alive and support each other. It’s really important to focus on your mental health and develop a sense of comfort and safety and a sense of who you are, because there is so much that can knock you down.”

“I think the more resources we have to express ourselves through art—and have that supported and encouraged—the better. And the more accessible, the better. I know a lot of people who have really benefited from things like art therapy.”

Providence Health Care’s mental health program is already planning the next patient art show for Mental Health Week in May 2026. Do you have or know of a venue in Vancouver who would be interested in hosting the next show? Contact Piotr Majkowski, Program Director, Mental Health here.