In 2009, as Dr. David Wood stood at the bedside of a patient who had just had an acute heart attack, he was faced with a dilemma. Although the blocked artery that caused her heart attack had been opened with a stent the night before, he was unsure if he should take her back to the procedure room to fix her remaining blockages or just send her home on medicine. Amazingly, no one in the world knew the correct answer.

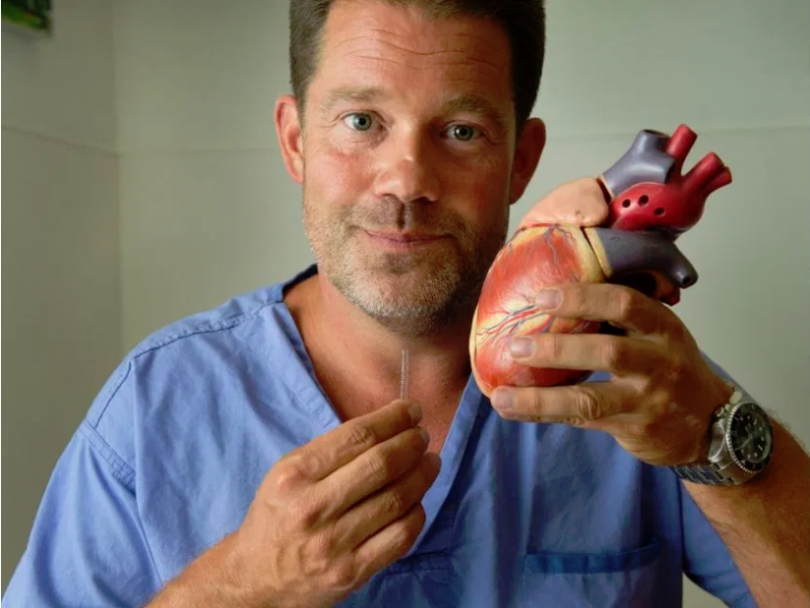

The heart is a muscular pump, approximately the size of your dominant fist, and it is supplied with blood by 3 tubes or arteries. Heart disease is the second leading cause of death in Canada. Also known as ischemic heart disease or coronary artery disease, heart disease refers to the buildup of plaque or cholesterol in the heart’s arteries that could lead to a heart attack, heart failure, or death. About 1 in 12 (or 2.4 million) Canadian adults age 20 and over live with heart disease. Every hour, about 12 Canadian adults age 20 and over die from heart disease.

Coronary angioplasty involves temporarily inserting and inflating a tiny balloon where the artery is blocked to help widen and open the artery. Angioplasty is usually combined with the permanent placement of a small wire mesh tube called a stent to help keep the artery open permanently. With an acute heart attack, the faster the blocked artery is opened, the greater the chance of surviving. Approximately half the time when someone presents with a blocked artery causing a heart attack, they also have blockages in their other arteries.

To answer the above question, working with the research teams at both Vancouver General and St. Paul’s Hospitals, Dr. David Wood, and Dr. John Cairns, former Dean of Medicine at UBC, wrote the protocol for the COMPLETE study. In collaboration with Dr. Mehta in Hamilton, over the next 7 years they enrolled 4041 patients at 140 centres in 32 countries. All patients had their culprit blocked arteries opened with a stent. Half the patients were then sent home on medical therapy and half the patients went back to the cardiac catheterization laboratory to have their additional blockages treated with coronary angioplasty and stenting. Patients could have their additional stenting procedure either early while they were still in hospital or come back a few weeks later to have the additional blockages fixed. On average all patients were followed for at least 3 years to determine which strategy would be best for preventing another heart attack or death.

The team presented their main results at the largest cardiovascular meeting in Europe, in Paris, September 1. Their results were also published in The New England Journal of Medicine on September 1.

The study found that the rates of cardiovascular death or recurrent heart attack were dramatically lower if all the additional blockages were fixed. Dr. Wood believes the results will dramatically change how heart attack patients are treated all over the world. To date, there has not been consensus on the best way to treat the remaining blockages.

In three weeks, the team will present the second part of their results in San Francisco at the largest cardiovascular meeting in North America. Standing with two of his patients in the cardiac cath lab at VGH earlier this week, Dr. Wood commented “now that we know we should fix all of the remaining blockages, it is important to understand if there is an optimal time to perform the second procedure. Should we perform it before the patient leaves the hospital or should they go home and come back a few weeks later after they have recovered from their initial heart attack?” Dr. Cairns remarked, “the results we present in San Francisco will further strengthen the evidence that all blockages should be fixed in the first 45 days after a patient’s initial heart attack.”