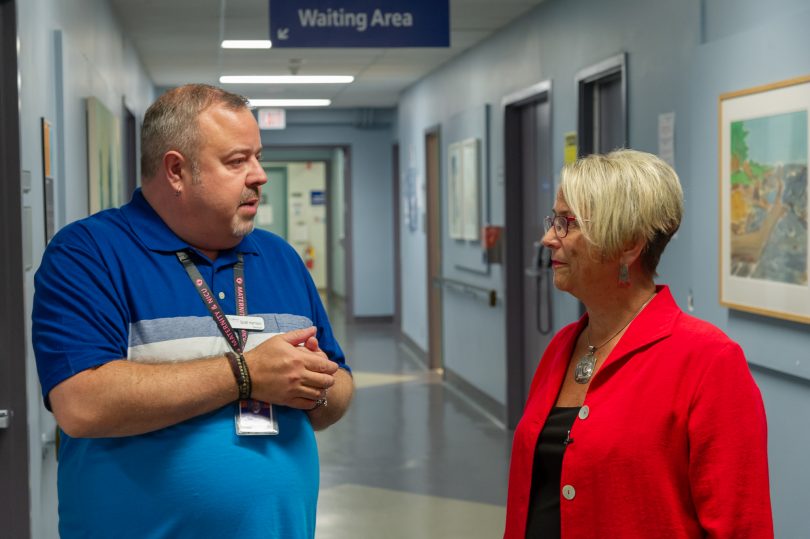

Scott Harrison is a senior administrator at St. Paul’s Hospital, responsible for programs from Urban Health to Maternity. Several years ago, he became a patient. On World Sepsis Day, he shares how he came close to dying from septic shock.

Scott Harrison is a senior administrator at St. Paul’s Hospital, responsible for programs from Urban Health to Maternity. Several years ago, he became a patient. On World Sepsis Day, he shares how he came close to dying from septic shock.

I started the summer of 2017 as a healthy 45-year-old health care professional with well-controlled diabetes.

During the summer, a new diabetic medication was added to my treatment plan – one of the new ‘wonder drugs’ for diabetes.

One possible side effect was increased risk of infection. Despite all precautions, I had the bad luck of contracting a bladder infection. This progressed to a kidney infection and didn’t get better, despite two rounds of antibiotic treatment. I developed a chest infection, which I attributed to a bad cold that was going around, and over the next few days I got worse and worse.

I ended up feeling so incredibly ill that I thought I was going to die. So late one night we rushed to our local Emergency Department. I felt breathless, had a fever, was dizzy and my heart was pounding. At triage, a nurse took my vital signs and immediately whisked me into the trauma room and I was quickly surrounded by nurses and doctors. I was attached to intravenous lines and monitors.

The diagnosis of septic shock was quickly delivered

The health team quickly diagnosed me with septic shock and launched into emergency treatment. Within half an hour of arriving I had deteriorated so quickly that I was intubated and prepped for transfer to the first available Intensive Care Unit (ICU) bed at another hospital.

On arrival in ICU a tracheotomy was performed to help me breathe. I was so sick I was packed in ice from armpits to ankles for days. My fever was so high they could not control it.

The culprit was, in fact, the new diabetic medication that had made me susceptible to infection. I was diagnosed with urosepsis and bilateral septic pneumonia. This led to multiple organ failure and acute respiratory failure.

I was critically ill for three weeks. I was ventilated, on circulatory support, had a tracheostomy and had a serious kidney infection plus severe bilateral pneumonia and multiple organ failure. Because of the long period of sedation and ventilation, I developed ICU delirium, so my initial memories were dream-like, odd and frightening. As I gradually re-entered the living world, I felt incredibly weak and unwell but I quickly started to recover. It was a frightening experience at times. However, the expert care I received from the team in ICU helped me enormously. They were so caring, compassionate and reassuring that I felt safe and well looked after.

The aftermath of my illness

I was so ill, I developed tracheal stenosis and tracheomalacia (narrowing and collapse of my airway). This will always be with me, so exertion leaves me quickly breathless. I had some difficulty adjusting to this critical illness and had PTSD due my delirium. I also have on-going pain and weakness on my left side due to a brain injury from lack of oxygen when I was at my sickest.

But I survived. I have overcome so much and am back to my full time work, my craft and hobbies and enjoying my friends and family and travelling again. My mobility is frustrating at times and the pain and breathlessness can be tiring, but I am alive.

My illness gave me perspective

I feel lucky to have survived septic shock when so many people don’t. Lucky to have come out of the experience relatively unscathed. Lucky to have been transferred to a great ICU and to have received the amazing care that I had. I am grateful for everyone at Eagle Ridge Emergency Department and Burnaby ICU for saving my life.

After a critical illness, you get an amazing opportunity to put things in perspective. Things that used to stress or bother me, don’t anymore. I have more time for people and a deeper understanding of what trauma feels like and it makes me better as a person and in my profession. The downside is I have less patience for what I think are trivial or selfish issues!

At its essence, it is a severe infection that leads to organ dysfunction and requires hospitalization, says Dr. Keith Walley, an ICU doctor at St. Paul’s Hospital and a leading sepsis researcher at the Centre for Heart Lung Innovation (HLI) at St. Paul’s. It can be triggered by any kind of infection, with the most common being pneumonia (a lung infection), or a bladder or urinary tract infection. But in fact every part of the body can get an infection severe enough to lead to organ dysfunction and septic shock. Some patients who die of other illnesses may actually have suffered sepsis. “Cancer patients may develop sepsis,” says Dr. Walley. “Most chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) deaths involve sepsis.”

Sepsis can progress to the most severe stage, septic shock – which is what Scott Harrison experienced. Septic shock symptoms include a serious drop in blood pressure such that there is not enough blood flow to vital organs – brain, heart, kidneys in particular. “Treatment is rapid recognition, early antibiotics and resuscitation with fluids, drugs to increase blood pressure and oxygen,” says Dr. Jim Russell, also a leading expert in sepsis and also with HLI. He is ranked #1 in the world in septic-shock expertise. “For those reasons, we emphasize that patients must get to their nearest emergency if they have symptoms of a severe infection because time is of the essence.”

Those at the highest risk of sepsis include diabetics, obese individuals and people who have had sepsis previously. They’re at 20 times the risk of the general population. The sepsis team at St. Paul’s recently found that diabetes triples the risk of dying of sepsis or septic shock. “The indigenous population is at risk for unknown reasons,” he says. “We want to look into why, and help them out.”

Dr. Walley’s research has led to theories that a protein in the body used to fight infection may be missing, or altered in some way so that the person is producing too much or too little of that protein. Drs. Russell and Walley are researching diabetics’ cholesterol and inflammatory responses as further possible triggers. They urge people to get their vaccines to help lower any risk of contracting sepsis or septic shock. This includes the annual flu shot and a pneumonia shot if your doctor says you’re in a high-risk category of that.

Symptoms of Sepsis

Courtesy: worldsepsisday.org