A nasal test for COVID-19 takes just a few seconds, but getting a long swab stuck up the nose isn’t an experience many people would describe as pleasant.

New research led by a team at St. Paul’s Hospital hopes to make the diagnostic process a bit more comfortable. Their study found that rotating the swab after it’s inserted into the nose – a step that makes the procedure take longer, and may increase patient discomfort – does not improve the quality of the sample collected and is therefore unnecessary.

Twist or no twist?

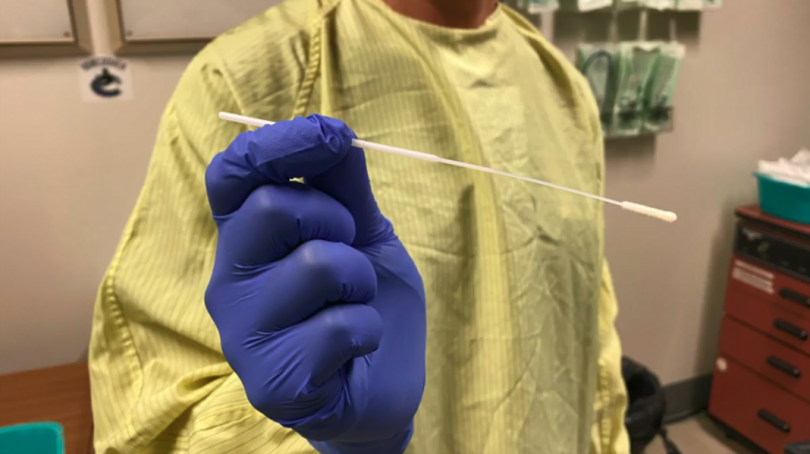

Nasopharyngeal swabs have been used for decades to diagnose respiratory infections. Getting a COVID-19 test involves a trained health care professional inserting a long, flexible swab into the patient’s nostril and along the nasal cavity – about seven centimetres deep – in order to collect a sample from the back of the throat, called the nasopharynx.

Once the swab makes contact with the nasopharynx, however, guidelines differ on what to do next. Some guidelines recommend rotating the swab in place for up to 10 seconds before removing it, while others say this is not necessary.

“Despite the widespread use of nasopharyngeal swabs, there is no universally-agreed-upon optimal technique to collect them,” says Dr. Victor Leung, Medical Director for Infection Prevention and Control at Providence Health Care. “Given that swab insertion and removal is invasive and uncomfortable, we wanted to better understand the impact of collection techniques on sample quality and patient experience.”

With that in mind, Dr. Leung approached Dr. Zabrina Brumme, the Laboratory Director at the BC Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS and a Professor at Simon Fraser University, for help conducting an experimental study to reveal whether rotation of the swab improved the quality of the specimen collected. Luckily, methods to assess this were already in place at SFU and the BC-CfE, and Dr. Brumme was quickly able to redeploy graduate students and staff to help out.

Their study was published October 14 in Open Forum Infectious Diseases.

Rotation doesn’t improve sample collection

In late summer 2020 the research team recruited 69 volunteers from among staff at St. Paul’s Hospital and assigned them to receive nasopharyngeal swabs either with or without rotation. The team asked the participants to rate their discomfort level and also measured the amount of DNA and RNA recovered on the swabs.

The results revealed that rotating the swab did not recover more DNA or RNA. Furthermore, responses from the participants suggested that rotation made the procedure less tolerable.

“Our first major conclusion, therefore, was that rotation of the swab does not improve sample collection quality and is therefore not needed,” says Dr. Leung.

Rotating the swab also takes longer, an additional disadvantage in the context of mass screening, the study notes.

Discomfort level varies by ethnicity

The researchers also found that discomfort during the swab test varied widely and differed by ethnicity.

When participants were asked to rate their discomfort on a scale from zero to 10, their responses ranged from 1 to 10. On average, Asian participants reported higher levels of discomfort during the procedure than participants who self-identified as White, a finding that the study says is likely attributable to differences in nasal anatomy among ethnic groups.

“Our second major conclusion was that care providers need to be sensitive to such differences, and more broadly underscores the importance of diverse participant representation in health research,” said Dr. Leung. “We are now working to translate our findings into an improved COVID-19 diagnostic experience for people getting tested.”

The study was funded by Genome BC.