It seems counterintuitive: initially treating patients suffering from an irregular heart rhythm with a surgical procedure in hospital rather than simply prescribing them with drugs.

But new research led by a St. Paul’s Hospital cardiologist has found that the minimally invasive procedure provides longer-lasting benefits than drugs as the first course of treatment for this common heart condition.

The study, published this month in the New England Journal of Medicine, recruited 303 highly symptomatic, but untreated, patients with atrial fibrillation (AF). This life-disrupting, chronic and progressive disease can increase the risk of a stroke or heart failure if the abnormal heart rhythm is not controlled.

“People in the study were severely affected by the disorder,” says Dr. Jason Andrade, principal investigator in the study and a cardiac electrophysiologist at St. Paul’s and Vancouver General Hospital. “While everyone experiences AF differently, some people can be severely affected or even incapacitated during an episode. Objective measures show it can be as intrusive to one’s quality of life as being on kidney dialysis.”

Problem heart muscles jiggle like jelly

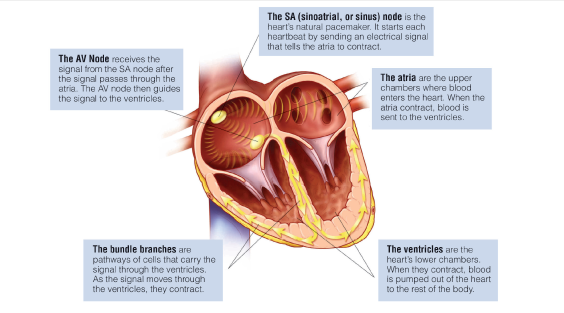

AF, caused by faulty electrical signals sent to heart muscles, affects some 700,000 Canadians and can cause numerous symptoms, including a rapid or irregular heart rate.

In a healthy heart, the upper chambers (atria) beat together in a co-ordinated rhythm, squeezing blood to the bottom chambers, or ventricles and then out to the rest of the body. But AF occurs when there is “fibrillation,” or quivering, of the atria in a way that’s been compared to a jiggling bowl of jelly. That quivering causes blood to pool and potentially clot, which could lead to a stroke or heart attack.

Ablation patients had less recurrence of AF

All patients in the study were implanted with a cardiac monitoring device to detect AF for 12 months.

Patients were randomly separated into two groups. One received drugs, while the other underwent a procedure called catheter ablation, typically reserved for people who don’t improve on anti-arrhythmic drugs.

The ablation group had a catheter inserted to the groin and fed to the areas of tissue in the atrial chambers that were causing the AF. The catheter destroyed the problematic tissue by freezing it (known as catheter cryoablation). The procedure only takes two hours, and is often done as a day procedure.

A year later, the recurrence of AF in the group taking the drugs was 68 per cent while in the ablation group, it was only 43 per cent. Dr. Andrade says the ablation group had a greater likelihood of being asymptomatic, and had a greater improvement in quality of life in the 12 months following treatment initiation.

Goal: reduce repeat hospital visits and costs

“We hope this study will change the way we treat people with symptomatic AF,” says Dr. Andrade, also an associate professor at UBC and Director of the AF Clinic at Vancouver General Hospital.

Currently, newly diagnosed patients receive drugs, then, if those don’t work, they’re switched to ablation.

While it may seem that the procedure as the initial response to AF is harder on the patient and the health-care system than drug therapy, Dr. Andrade says over the long term, it may be more beneficial than drugs.

“Ablation is an up-front cost to the health system,” he agrees. “But the goal is to alter the disease such that the number of return hospital visits these patients need to have are reduced, as they can be hard on them and can stretch hospital resources.”

Condition builds “like a snowball”

Indeed, AF is one of the costliest chronic health conditions in Canada. Research published this October in the Canadian Journal of Cardiology paper (to which Dr. Andrade contributed) says the direct annual cost of AF, adjusted for 2020 dollars, was $956 million, part of which is due to the some 77,000 ED visits each year.

While medicines are cheaper than surgery in the short term, “if they’re not working and people keep going back to emergency rooms or miss work or aren’t coping well, that’s going to have a huge cumulative cost to society.”

“AF is like a snowball,” he continues. “It builds and worsens over time. If we start with an ablation, we may be able to fix it early, which could potentially reduce the risk of stroke and other heart problems down the road.”

The study took place at 18 Canadian sites, including St. Paul’s, Vancouver General and Royal Jubilee Hospital in Victoria.