An update to this story, first published a year ago: Since the OPS opened inside St. Paul’s Hospital in 2021, staff have supervised a total of 3,625 patient visits. They successfully reversed a total of 167 overdoses. No one has been admitted to a higher level of care and no one died. Meanwhile, staff are working to hire more peer support workers to staff the site 24 hours a day.

Canada’s first Overdose Prevention Site (OPS) inside an acute-care hospital is celebrating a milestone birthday today.

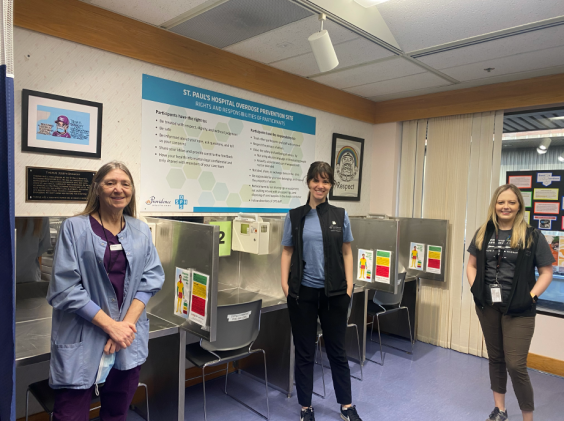

The OPS, located inside St. Paul’s Hospital, turns one.

There is much to celebrate.

Since February 1, 2021, the OPS saw close to 2300 visits from hospital patients who came to use their drugs in a safe, hygienic and nurse-supervised space. Another 1300 patients visited to collect sterile supplies the OPS provides for safer smoking and injection.

The aim is simple: to prevent drug overdoses and deaths.

On that front, the news is also good: Of the visits, there were 90 overdoses, all successfully reversed. None of those patients required a transfer to the Intensive Care Unit.

That is 90 lives saved as the illicit drug overdose, grimly known as the “other” pandemic, rages in British Columbia, claiming on average 6.5 lives a day.

A non-judgmental approach to substance use to reduce its harms

The innovative OPS is part of harm-reduction services at St. Paul’s, which neither condones nor condemns use, but recognizes the reality of the toxic-drug situation in BC and works to minimize its human cost.

“St Paul’s Hospital has been ground zero for the overdose epidemic in Vancouver,” says Scott Harrison, Director of Urban Health, HIV and Substance Use at Providence Health Care. “Many patients continue to use while admitted. As part of our commitment to harm reduction, we took the pragmatic approach of developing an in-hospital OPS to help prevent patients from using in secluded areas where help is not readily available.”

Trying to prevent using drugs alone

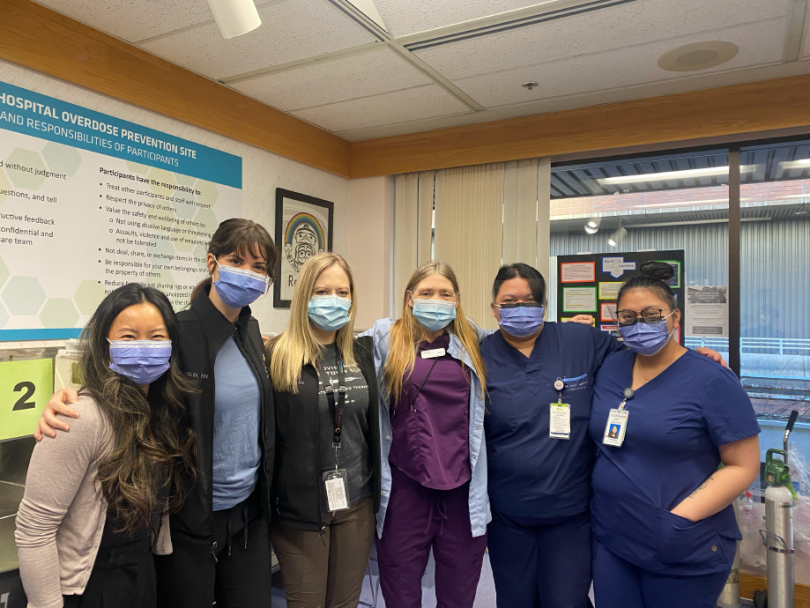

The site is for both inpatients and outpatients, says Carlin Patterson, Clinical Nurse Leader of the St. Paul’s Hospital OPS and Urban Health Nurse Educator.

“The OPS is an alternative to using drugs alone in the hospital,” she says.

Elizabeth Dogherty, Clinical Nurse Specialist also with Urban Health, concurs. “It can be difficult for individuals who use substances (outside of the hospital) to abstain from using while admitted, which can be a period of increased stress and pain. We are trying to prevent patients who happen to use drugs from overdosing alone in hospital stairwells and washrooms.”

“I am an ally.”

Karen Scott, a peer support worker at the OPS, is fully aware of the dangers of using alone. She used to do so herself during the decades that she consumed illicit drugs. “I used anything that would numb the pain” of personal traumas that she confronted as a young person.

Abstinent for the past five years, she acts as a liaison between the patient and the clinical team, escorting patients to the site and providing no judgment.

She listens to their stories and sometimes shares her own.

“I am an ally. I meet patients where they are.”

The St. Paul’s OPS is nurse led, which distinguishes it from other community-based overdose prevention sites. Two nurses are on site during the 10 am to 8 pm operating hours. Black, the peer-support worker, is also in hospital on weekdays to provide additional support for the site.

The OPS offers the following:

- Witnessed consumption of injection drugs;

- Overdose response if needed;

- Education on safer injection practices and sterile supplies;

- Drug testing for fentanyl and benzodiazepine contamination; and

- Take-home naloxone kits.

“Providence strives to lead in ethical, pragmatic and humanizing care for people who use substances,” says Harrison, “and always with the intention of engaging patients in treatment that separates them from the toxic drug supply in BC.”