The life of a teenager is often go, go, go, so it is important that they get enough sleep. However, that’s easier said than done. Teenagers are particularly susceptible to a phenomenon known as “social jetlag”, whereby someone’s natural body clock (when they naturally sleep or wake up) is not aligned with their socially determined clock (when they are able to sleep or wake up).

Centre for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences (CHÉOS) Scientist Dr. Annalijn Conklin teamed up with colleagues from UBC, including Masters student Kexin Zhang, to determine whether there is a link between social jetlag and the consumption of ever-popular sugary drinks among teenagers.

“Adolescents are at a unique phase of human development that involves a number of biological changes, including a change to their biological clocks (circadian rhythm). Specifically, adolescents experience a shift towards later bedtimes and later wake times, and shorter sleep periods,” said Dr. Conklin, Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, UBC. “At the same time, adolescents go through social changes that include more academic and other responsibilities, which put pressure on their waking hours and may prevent them from waking up as late as their biology dictates.”

Digging into the data

Sugary drinks, more formally known as sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs), have been linked to health issues like obesity and type 2 diabetes among adolescents. As such, it’s important to understand and respond to exactly what drives their consumption.

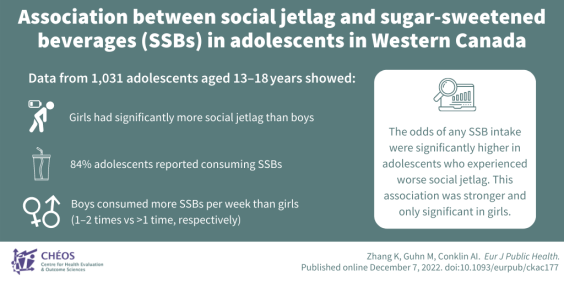

Using self-reported data from 1,031 adolescents aged 13–18 who completed the British Columbia Adolescent Substance Use Survey, Dr. Conklin found that almost two-thirds of the participants experienced over an hour of social jetlag. Put simply, these respondents experienced at least an hours’ discrepancy between when their body biologically wanted to sleep and wake (hours on a ‘free day’), and when they actually slept and woke (hours on a weekday). Furthermore, more than 80 per cent of the teens reported they drank SSBs.

Upon further investigation, SSB consumption was found to be associated with social jetlag: Teenagers experiencing at least one hour of social jetlag were more likely to drink SSBs, compared with teenagers experiencing less than one hour of social jetlag.

The team then dug deeper to determine if there was a difference between teenage boys and girls.

“It is always important to study sex and gender differences as there is a large body of research showing that sex and gender are fundamental determinants of health outcomes and health risk factors,” Dr. Conklin explained. “In the case of social jetlag, there are biological sex differences in the circadian rhythm and the physiological manifestation and effects of stress. There are also socially constructed gender differences in the roles and expected behaviours regarding the performance of activities and responsibilities that demand time away from sleep.”

In this study, girls experienced more social jetlag (1.64 hours) than boys (1.52 hours). In addition, while boys reported consuming sugary drinks more frequently than girls (once or twice a week compared with less than once a week), the association between social jetlag and sugary drinks was only significant among girls. In fact, girls who experienced at least two hours of social jetlag were almost twice as likely to drink SSBs than girls who had no social jetlag.

Sweet dreams > sweet tooth

Many parts of the western world have been subject to public health campaigns and interventions aimed at reducing excess sugar intake to combat issues including tooth decay and obesity. You can see just a few examples from the UK, USA, and Canada. But if Dr. Conklin’s latest study shows us anything, it’s that we need to think outside the box. Public health strategies need to consider the interplay between factors, like social jetlag, and sugar intake, and respond accordingly.

“As someone trained in public health, my solutions would include considerations of start times for school and/or work that better align with the biological clocks of teenagers,” said Dr. Conklin. “On the individual level, education and awareness about general biology is important, as well as the importance of ‘getting enough’ sleep and at the ‘right time’ for your stage of development. Part of this education would also need to include sleep hygiene strategies, including no screen time about an hour before bed and the absence of any light in the room while sleeping, among other practices.”

Reducing social jetlag could be a win/win for teenagers and public health: Teenagers get a better night’s sleep and experience improved health outcomes, while the public health system encounters fewer incidences of preventable, SSB-related diseases. But research is just the beginning.

“Effecting change requires policy- and decision-makers to be engaged with the issue. There is some work being done in the US with policy-makers to amend the school start times for teens for better sleep alignment and those results appear promising,” concluded Dr. Conklin.

– By Hannah Branch

This story originally appeared on the CHEOS website.

Related story: Shedding light on sleep in adolescence