When Warren woke up one day recently, he felt unusually dizzy. He brushed it off, thinking he had gotten out of bed too fast.

But the sensation didn’t go away. Soon he was experiencing a clutch of other unpleasant feelings: unsteadiness, a feeling of being off balance, and a touch of nausea.

Like a hangover without the alcohol

“I was a bit woozy, like I was having a hangover, and it felt like the room was spinning. Only, I hadn’t drunk anything,” says the Vancouver retiree.

The feelings became so uncomfortable he limited his usual activities. He didn’t want to drive, or even walk. “I just wanted to lie down,” says Warren, whose name has been changed for privacy. Not much of a pill taker, he took a Gravol for the nausea.

Warren was experiencing vertigo, one of what health insurer Ontario Blue Cross estimates are 1.5 million Canadians who have symptoms at any given time.

Problems with the inner ear system

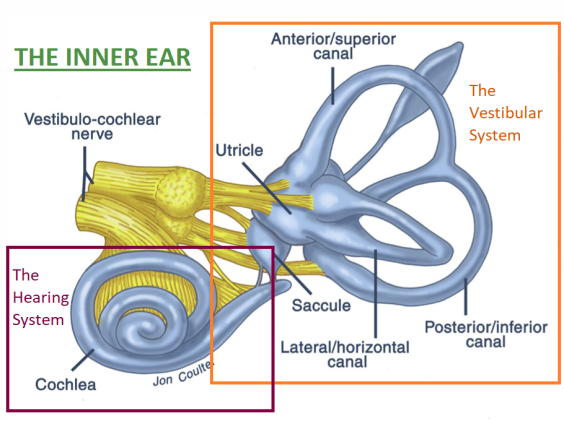

Vertigo occurs for many different reasons, including when something goes amiss in a part of the complex inner ear made up of the hearing (cochlea) and balance (vestibular) systems, says Jolene Harrington, Registered Audiologist with the Audiology Program at St. Paul’s Hospital. “This system is what helps keep us balanced.”

“The five parts in each ear’s vestibular system work together as a team. If you lose one, the other side can compensate with the help of your brain.”

The condition can be debilitating for some, says Harrington, causing nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other unpleasant symptoms. “I have seen patients unable to work and who feel scared to leave their home from risk of falling. It can reduce their social activities too.”

Warren was fortunate. His symptoms disappeared a few days later, as quickly as they had come on.

However, some people may go on to need the professional treatment that Harrington and the Audiology program provide, depending on the cause.

There are many causes of vertigo, she says, with over 10 related to the inner ear alone. One is labyrinthitis, an inflammation of the inner ear (or labyrinth). Typically, it goes away on its own, but some patients may receive medication to treat an infection that may be the cause of it.

Dislodged inner-ear crystals

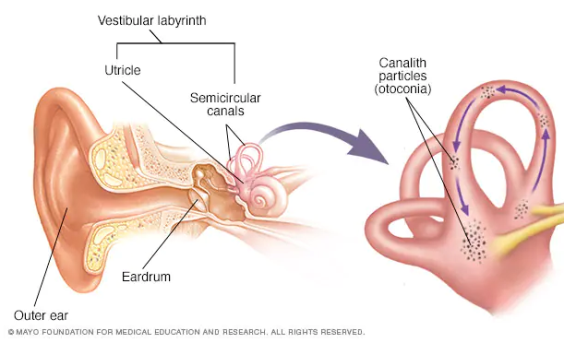

One of the most common causes of vertigo is benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV for short). It happens when calcium-carbonate crystals that normally sit in a part of the inner ear become dislodged and float into the one of the inner ear’s semicircular canals.

The crystals are part of the gravity sensors in the inner ear and help keep us balanced, explains Harrington. “When they float (as our inner ear is filled with fluid) into a part of the inner ear where they don’t belong, we feel the sensation of dizziness/vertigo, spinning and feeling off balance.”

“Usually the sensations are short lived until the person moves again causing the dislodged crystals to go floating again.”

If the sensations persist, certified audiologists in vestibular assessment and management, or some physiotherapists who have further studied the balance system might next try positional tests, including the Dix-Hallpike test, where they turn the ,patient’s head 45 degrees to the left or right and have them lie down to find out if those movements are the cause.

The eyes have it

Because the eye-ear connection is vital to balance and stability, practitioners use the eyes to know what the ears are doing. The eyes are the windows to the inner ear balance sensors.

To do this, they place infrared goggles on the patient to a get a more precise look at eye movements and better work out if the vestibular system is involved in the cause. In the cases of BPPV, which semicircular canal is affected. Using these goggles, connected to a computer, the audiologists can detect involuntary, rapid movements of the eyes (called nystagmus).

The patient is in a dark room with the eyes covered to avoid fixating their eyes on any point. The specialist may detect nystagmus, where “it looks like the eyes are jumping around.”

Barbecue roll

If this is so, a repositioning manoeuver might be needed. And what the maneuver will be depends on which semicircular canal(s) is involved in the BPPV. “We basically flip the person around to get the crystals back into place,” says Harrington. “For instance, we have what we call the barbecue-roll maneuver. We have the patient start on their back and then have them roll to one side, then onto their belly, then onto the other side, and then possibly keep going depending on what’s happening with the eyes – like rolling on a barbecue spit.”

Other inner ear disorders that cause vertigo may be harder to treat, like Ménière’s Disease. Along with vertigo, people with this typically have tinnitus (ringing in the ear) and hearing loss. In very rare cases, people whose Ménière’s is extremely debilitating may require surgery called a labyrinthectomy. It is a last resort for treatment of this inner ear disease. The surgery removes vestibular end organs so the brain no longer receives signals from those sections of the inner ear that sense motion, head position, and spatial orientation.

In general, doctors and audiologists take a thorough case history to help determine the cause of the vertigo. It could be related to a multitude of causes, included but not limited to cardiac or neurological issues, or, as in Warren’s case, could be a one-time case that resolves itself.

But, as he knows, it is never pleasant.

If you are experiencing vertigo or other balance and dizziness sensations, Harrington suggests visiting www.balanceanddizziness.org, a non-profit website for patients.